CHAPTER FOUR

THE JESUS CONNECTION

Throughout the history of western civilization, no singular event has so profoundly transformed the course of human existence, as did the life cycle of Jesus the Nazarene. For almost two thousand years, men and women throughout the world have attempted to unravel that mysterious event, to uncover its arcane meaning, to plumb its unfathomable depths.

From this endeavor, Nietzsche also did not abstain. His vehement dislike of the traditional and institutionalized forms of Christianity reflected a frustration with the intractable challenge of finding meaning in the life of the Nazarene. The truth in Christianity, Nietzsche thought, must be rooted in its primitive state; rooted exclusively in the personal actions and subjective experience of its founder Jesus. Nietzsche believed that Jesus had achieved an almost infantile type of identification with his external world; Jesus had perfected an inner world, undisturbed by outer realities. He had, as Nietzsche said, “the profound instinct for how one would have to live in order to feel oneself 'in Heaven', to feel oneself 'eternal', while in every other condition one by no means feels oneself ' in Heaven'.”1 Although Nietzsche surely considered Jesus’ inner world unnatural and delusional he apparently could still respect it. His explanation illustrates this fact:

One could, with some freedom of expression, call Jesus a 'free spirit' - he cares, nothing for what is fixed: . . . The concept, the experience 'life' in the only form he knows it, is opposed to any kind of word, formula, law, faith, dogma. He speaks only of the inmost thing: 'life', 'truth', or 'light' is his expression for the inmost thing – everything else, the whole of reality, the whole of nature, language itself, possesses for him merely the value of a sign, a metaphor. – On this point one must make absolutely no mistake, however much Christian, that is to say ecclesiastical prejudice, may tempt one to do so: such a symbolist par excellence stands outside of all religion, all conceptions of divine worship, all history, all natural science, all experience of the world, all acquirements, all politics, all psychology, all books, all art - his 'knowledge' is precisely the pure folly of the fact that anything of this kind exists. He has not so much as heard of culture, he does not need to fight against it - he does not deny it. . . . The same applies to the state, to society and the entire civic order, to work, to war - he never had reason to deny 'the world', he had no notion of the ecclesiastical concept 'world’. . . . Denial is precisely what is totally impossible for him. - Dialectics are likewise lacking, the idea is lacking that a faith, a 'truth’ could be proved by reasons (- his proofs are inner 'lights', inner feelings of pleasure and self-affirmations, nothing but 'proofs by potency' -). Neither can such a doctrine argue: it simply does not understand that other doctrines exist, can exist, it simply does not know how to imagine an opinion contrary to its own. . . . Where it encounters one it will, with the most heartfelt sympathy, lament the 'blindness' - for it sees the 'light' - but it will make no objection . . .2

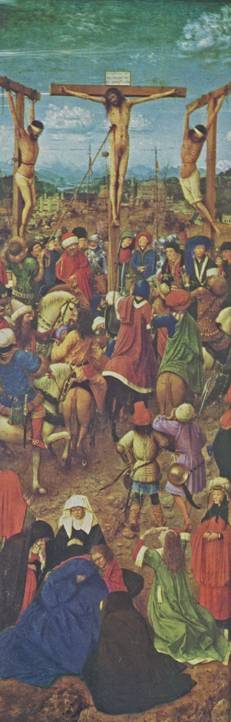

Nietzsche never accepted that Jesus' death was a ransom for the guilt of others. Jesus had died because of his own guilt; he had even provoked his own death according to Nietzsche. In a subjective sense, Jesus meant to illustrate by his own example how anyone could experience the ‘kingdom’ as a child of God:

This 'bringer of glad tidings'

died as he lived, as he taught - not to 'redeem mankind' but to

demonstrate how one ought to live. What he bequeathed to

mankind is his practice: his bearing before the judges, before

the guards, before the accusers and every kind of calumny and mockery – his

bearing on the Cross. He does not resist, he  does

not defend his rights, he takes no steps to avert the worst that can happen to

him - more, he provokes it. ... And he entreats, he suffers, he loves with those, in those

who are doing evil to him. His words to the thief on the cross contain

the whole Evangel'. That was verily a divine man, a child of God!' -

says the thief. 'If thou feelest this' - answers the

redeemer - 'thou art in

does

not defend his rights, he takes no steps to avert the worst that can happen to

him - more, he provokes it. ... And he entreats, he suffers, he loves with those, in those

who are doing evil to him. His words to the thief on the cross contain

the whole Evangel'. That was verily a divine man, a child of God!' -

says the thief. 'If thou feelest this' - answers the

redeemer - 'thou art in

As another example of Nietzsche's sagacity, he perspicaciously points out that injecting a concept of resurrection into the Gospel accounts of Jesus' life completely preempts any concept of his natural death. His death might be real, but not in his world:

The '

For Nietzsche, the truth in Christianity had its beginning and its end in the subjective and childlike experience of Jesus. Any attempt to convert Jesus’ solipsistic experience into an objective reality negates its essential subjective nature and thereby falsifies it. In pursuing its ‘will to power’, Nietzsche believes, Christianity did exactly this; it attempted to objectify the subjective truth and thereby falsified its meaning and significance.

- To resume, I shall now relate the real history of Christianity.

- The word 'Christianity' is already a misunderstanding—in reality there has been only one Christian, and he died on the Cross. The 'Evangel' died on the Cross. What was called 'Evangel' from this moment onwards was already the opposite of what he had lived:5

Jesus’ subjective experience, correctly interpreted, must be symbolic. Objectively, a figurative example others might emulate in a literal sense subjectively. While never a true possibility for individuals objectively, resurrection was always truly possible for an individual subjectively. This was the symbolic truth underlying Jesus’ own resurrection.

Nietzsche explains that in failing to understand correctly the true symbolic meaning of Jesus’ death and resurrection, in missing the essential solipsistic nature of the event Christianity attempted to convert that event's inherent symbolism into an objective reality. To compensate for this initial mistake and to proselytize an increasingly diverse multicultural population, Christianity had to assign historical significance to its invented traditions. Substituting these fabricated traditions for unsubstantiated historical events further debased the symbolic truth of Jesus’ resurrection and promoted the proliferation of irrational beliefs about its nature and significance:

On the contrary: the history of Christianity - and that from the very death on the Cross – is the history of progressively cruder misunderstanding of an original symbolism. With every extension of Christianity over even broader, even ruder masses in whom the preconditions out of which it was born were more and more lacking, it became increasingly necessary to vulgarize, to barbarize Christianity - it absorbed the doctrines and rites of every subterranean cult of the Imperium Romanum, it absorbed the absurdities of every sort of morbid reason. The fate of Christianity lies in the necessity for its faith itself to grow as morbid, low and vulgar as the requirements it was intended to satisfy were morbid, low and vulgar. As the Church, this morbid barbarism itself finally assumes power - the Church, that form of mortal hostility to all integrity, to all loftiness of soul, to discipline of spirit, to all open-hearted and benevolent humanity. – Christian values - noble values:6

While Nietzsche never attempts to hide his vituperative vilification of the Church, as the institutional outgrowth of Jesus' death and resurrection, he does not disparage Jesus in the same manner. Almost sympathetic to his innocence or naïveté, Nietzsche appears to believe Jesus would have outgrown his childlike egocentrism had he lived long enough.

Believe me, my brothers! He died too early; he himself would have recanted his teaching, had he reached my age. Noble enough was he to recant. But he was not yet mature.7

Moreover, there is almost a degree of sadness in the following statement by Nietzsche:

One sees what came to an end with the death on the Cross: a new, an absolutely primary beginning to a Buddhistic peace movement, to an actual and not merely promised happiness on earth. For this remains - I have already emphasized it – the basic distinction between the two decadence religions: Buddhism makes no promises but keeps them, Christianity makes a thousand promises but keeps none.8

In this passage from The Anti-Christ, Nietzsche seems to suggest that Jesus, if he had grown up in a different environment—one free from the Hebraic concepts of sin and guilt, he could have ushered in a new era of happiness for the western world. Nietzsche appears to believe that a man as spiritual as Jesus, once he had matured would "no longer speak of 'the struggle against sin' but, quite in accordance with actuality, 'the struggle against suffering'."9 Jesus would have moved, in Nietzsche's own words, "beyond good and evil."10 His life and death would have affirmed all that was natural in human existence. In this regard, Nietzsche believed, Jesus could have enlightened the western world as Buddha had done in the East.

In this respect, any historical connection between Jesus and Nietzsche is bidirectional in its influential effect. The legacy of Jesus' life profoundly shaped much of what Nietzsche thought about the world and all human life in it. The development of his philosophy was, in itself, not immune from the effects of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection. This idea, this connection—this Jesus Connection is the central theme of this final chapter. It will focus on a theory that synthesizes Nietzsche's idea of the Eternal Recurrence with a scientific understanding of the relationship that might exist between human consciousness and the universe—a universe in which time and space are unified.

The theory, set forth in this final chapter, has its foundation on the three premises initially discussed in chapter one of this paper. First, any concept of human existence independent of the central nervous system is completely meaningless. Second, the central nervous system is a physical phenomenon of the material universe and governed by the invariant natural laws of that universe. Third, the universe really exists and the nervous system experiences it as a multitude of natural phenomena.

The nature of Jesus' messianic experience and its cultural impact on western society is such that any effort to reinterpret that experience in terms of current cosmological and neurological theories is tantamount to reinterpreting all human existence in relationship to these same theories. Implicit in this approach is the assumption that cosmology and neurophysiology are existential complements of each other and therefore provide the proper context in which to understand completely Jesus' life, death, and resurrection.

To further our understanding of the messianic experience and resurrection of Jesus requires an expanded concept of human consciousness, an abstraction of consciousness that recognizes its causal connection to patterns of synaptic activity within the human brain. The neurological concept of a brain consciousness will encompass the entire range of human consciousness. It denotes a tripartite division in which human consciousness is partitioned into three states: (1) sub-consciousness (no conscious awareness), (2) semi-consciousness (sleeping and dreaming), and (3) cognitive consciousness (conscious self-awareness). This abstraction connotes a trinity of consciousness in human beings. Notwithstanding its theological overtones, this approach to understanding human consciousness is actually a modern concept. The association of brain states with states of consciousness had eluded most ancient philosophers. Only within the past century and a half has science truly come to appreciate the strong link between the two. In general, the origins of human consciousness had remained an arcane secret to the western mind. From pre-classical antiquity, philosophers had attempted to answer the questions and to explain the ambiguity of its origins. Unrelenting in its mystery, its potential capability had always remained a topic of speculation for the human mind.

The sub-conscious state—that first partition in the tripartite concept of brain consciousness, although inaccessible to self-awareness, is still critical to the overall survival of all sensory awareness. From this sub-conscious level of synaptic activity, the brain controls many life-supporting functions such as regulating heart rate, breathing rhythm, and body temperature. Moreover, at this sub-conscious level of brain consciousness, unnoticed by itself, the brain processes much of the sensory data associated with the initial stages of seeing, smelling, behaving, feeling, thinking, and speaking. Finally and most remarkably, this sub-conscious level is hypothetically the source of unending life in an eternal cosmos. Having come into existence as a highly improbable event in space and time, this sub-conscious state of brain consciousness is thereafter associated with a simple arithmetic comparison between itself and nonexistence. Always discovering the unity of its self in this comparison, the sub-conscious state continuously reassembles itself by extending that unity concept to a particular instantiation of that unit reciprocally. In this manner, the sub-conscious state of brain consciousness continues to share in the space-time attribute of a continuum. This aspect grants it a temporal transcendence and enables it to exist eternally within the space-time continuum. Objectively inaccessible because of its displacement in space-time this sub-conscious state of brain consciousness, tattooed by its subjective experiences, preserves those transcribing moments in space-time eternally. Those discrete moments then populate a spiritual dimension within the universe, a spiritual realm where unending life is a daily occurrence. The synergy between the sub-conscious and semi-conscious states of brain consciousness gives meaning to the concept of resurrection. Although inaccessible to the cognitive conscious state of brain consciousness, this synergy endows humanity with a spiritual power that enables it to share in the divine nature of space and time.

The second level of brain consciousness—that is the semi-conscious or dreaming state has especially captivated the imaginations of many people throughout history. For instance, two thousand years ago it was common for individuals in the Greco-Roman culture to engage in the practice of incubation. According to Jacques Le Goff, “Much use was made of the practice of stimulating dreams by incubation, associated with the temples of certain healing gods such as Serapis and especially Asclepios.”11 The ancient practice of incubation involved an individual sleeping in the temple of a god with the expectation that doing so would facilitate a nocturnal visit, inspiration, or sexual encounter with that divine being. Thus, pagans did not consider sleeping an unconscious or semiconscious state. Quite to the contrary, they considered it a far more meaningful state of consciousness. Even Tertullian, a church father writing in the early part of the third century "refers to dreams (somnia) as the business of sleep (negotia somni). Thus dreaming, though it occurs in sleep, is considered a part of the active life."12 As a result of its sublime effectiveness, ancient pagans considered sleep a divine state of consciousness. As Nietzsche writes, "This is the Apolline dream state, in which the daylight world is veiled and a new world, more distinct, comprehensible and affecting than the other and yet more shadowy, is constantly reborn before our eyes."13 The acceptance of dreams and oneiromancy was apparently widespread throughout the pagan culture of the Greco-Roman world. According to Le Goff, “Both ordinary people and intellectuals considered the vast majority of dreams to be true and reliable."14

While the sub-conscious and semi-conscious states of brain consciousness are complementary and form a synergistic relationship that permits them, effectively, to transcend time, the third partition of brain consciousness—that of the cognitive consciousness state is distinctly aware of its own subordination to the passage time. It recognizes ageing in itself and others. It perceives time as the great destroyer, the increasing entropy of the universe—its unrelenting enemy. As the information associated with subsequent synaptic patterns always replaces or updates the information associated with previous patterns, this perception is constantly confirmed and reinforced in cognitive consciousness by this asymmetry in human memory. Responsible for generating the ‘self’ and imbuing it with self-awareness, this third state is obsessed with the inexorable passage of time. This dissonance between self-awareness and the other two less focused states of brain consciousness is only resolved through a faith in its potential resolution. Completely inaccessible from an objective perspective, its resolution is a completely subjective experience. Acquiring consciousness awareness of this resolution is the central point to the resurrection story of Jesus Christ.

To discover the true reality and to identify the actual events that culminated in the first Easter require an understanding of human memory, its creation processes and its relationship to space-time. Within the central nervous system and especially within the brain itself there is a biochemical process for converting present perceptions of sensory data into the permanent memories. These reinforced patterns of synaptic activity encode information about current experiences and convert them into long and short-term memories. The biochemical process tattoos the memories into the synaptic connections of a given neuron discretely at a given location on the space-time continuum. Recalling a particular memory requires the cognitively conscious state of brain consciousness to access those neurons that had their synaptic connections altered by converting the original experience into a memory. While a cognitive consciousness is available to remember the selected event, it remains only a memory of a specific event at a particular location in space and time. If the cognitively conscious state of brain consciousness is no longer available to remember the event then the combined action of the sub-conscious and semi-conscious states of brain consciousness can reassemble a new cognitive consciousness at that previous location in space-time. This is possible because for any moment in the space-time continuum, our memory of the moment before and our anticipation of the moment after eternally bounds every present moment we experience. From this fact, it becomes clear that our lives are actually comprised of a given number of eternally present moments. As Nietzsche writes, "An illusion that we, utterly caught up in it and consisting of it—as a continuous becoming in time, space and causality, in other words—are required to see as empirical reality."15 In this manner, instantaneous patterns of synaptic activity that encode specific memories will coincide eternally with an emerging sense of being oneself at that given location on the space-time continuum.

In its conscious acceptance of dreams as harbingers of the future, the pagan mind promoted a subconscious stratum that could blend the realities of dreams with the actual realities of life seamlessly. Within this subconscious echelon, the pagan mind could easily transmute the imaginary into the real without any contradiction. This capacity to conflate dreams into reality became a significant feature on the mental landscape of the ancient world. This mental aptitude manifested itself in a panoramic pagan consciousness that encompassed a wider range of symbolic significance to imaginary stimuli than contemporary consciousness does. This empowered the ancient mind to ignore questions of actuality when expedient or meaningful to do so.

Within this pagan culture and against this panorama of pagan consciousness, the early Christians sought to preserve their recollections of Jesus. Writing many years after Jesus’ death, in fact more than a generation later, the authors of the canonical gospels could have innocently conflated the disciples' remembrances of dreams with their recollections of actual events. Within the context of this first-century pagan culture, such a conflation of memories could have occurred without any cultural condemnation or literary censure. Without any desire to deceive their readers, the authors of these gospels could have compiled the oral legends of Jesus, both real and imaginary, into a written narrative in which the assimilation of the imaginary into the real remained hidden in the text.

It is in this context that we should reexamine the biblical narratives of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection. To illustrate this fact consider that the Synoptic Gospels, on twelve occasions, emphasize that Jesus or his disciples were asleep at critical moments in their narrative accounts.15 On five other occasions, the Gospels refer to the dead or dying as being asleep.16 These references to states of semi-consciousness imply that only by interpreting the narratives with respect to overall brain consciousness, is it possible to understand completely their mysterious truth. Moreover, if the recollections of disciples’ dreams actually are an integral part of the written record than the dreams of Peter, James, and John are the most significant recollections recorded in the biblical writings. In repeatedly describing the imaginary events of their dreams, these three disciples may have provided Christianity with an enduring source of power and faith.

According to Jacques Le Goff, “Significant dreams in the Bible tend to establish a link between heaven and earth rather than between the present and the future as in pagan oneiromancy. Time belongs to God alone. The dream, rather than reveal the future, puts the dreamer in contact with God.”17 This perspective helps to clarify a perplexing issue in the history of Christianity. If the recollections of the disciples' dreams had not been included in the gospel accounts, questions about the divine nature of Jesus most likely would have remained obscured in pagan ambiguity regarding such issues. If the disciples had not interpreted their dreams about Jesus the man as a contact with God the creator, Christianity might have avoided the torrent of theological controversy that surrounded the true nature of Jesus. The heresy of Docetism best typifies this early confusion over the exact nature of Jesus. In his book, Lost Christianities, Bart Ehrman describes Docetism:

Docetism was an ancient belief that very early came to be proscribed as heretical by proto-orthodox Christians because it denied the reality of Christ’s suffering and death. Two forms of the belief were widely known. According to some docetists, Christ was so completely divine that he could not be human. As God he could not have a material body like the rest of us; as divine he could not actually suffer and die. This, then, was the view that Jesus was not really a flesh-and-blood human but only “appeared” to be so . . . . For these docetists, Jesus’ body was a phantasm.

There were other Christians charged with being docetic who took a slightly different tack. For them, Jesus was a real flesh-and-blood human. But Christ was a separate person, a divine being who, as God, could not experience pain and death. In this view, the divine Christ descended from heaven in the form of a dove at Jesus' baptism and entered into him;7 the divine Christ then empowered Jesus to perform miracles and deliver spectacular teachings, until the end when, before Jesus died (since the divine cannot die), the Christ left him once more.

________

7See, e.g., Mark 1:10. In Greek, the verse literally says that the Spirit descended "into" Jesus.18

By applying this theoretical approach, by incorporating states of brain consciousness into the biblical accounts of Jesus we can clarify many of the strange and mysterious events surrounding his life, death, and resurrection. Many of the miracles ascribed to Jesus would easily fit into a category of recollected dreams. If these disciples discussed their dreams with other followers, it was not to relate some imaginary event or some unreal or insignificant occurrence. These dreams were real. They had a purpose. Each disciple really had experienced them and he or she only meant to share them with others. Those other followers would have accepted these dreams as authentic events, as validated truths. There would have been no reason to do otherwise, no reason to doubt. It was a different culture, miracles could happen and dreams could be real. To discount the recollections of disciples’ dreams by ascribing them only to disciples’ midnight imaginings is to allow a contemporary bias to taint a proper understanding of that society and its culture. It is important to note that after Jesus’ death, sharing their common recollections of dreams about Jesus would have been a great source of comfort to the early disciples. Told repeatedly, many times throughout the following years, these recollections of dreams became recollections of events. In the absence of the original disciples, it would have been natural to compensate for their missing presence and passion by converting their dreams into actual occurrences.

One noteworthy example of this possibility is the account of Jesus walking on the water as recorded in Matthew, Mark, and John. Matthew reports the following account:

And when he had sent the multitudes away, he went up into a mountain apart to pray: and when the evening was come, he was there alone. But the ship was now in the midst of the sea, tossed with waves: for the wind was contrary. And in the fourth watch of the night Jesus went unto them, walking on the sea. And when the disciples saw him walking on the sea, they were troubled, saying, It is a spirit; and they cried out for fear. But straightway Jesus spake unto them, saying, Be of good cheer; it is I; be not afraid. And Peter answered him and said, Lord, if it be thou, bid me come unto thee on the water. And he said, Come. And when Peter was come down out of the ship, he walked on the water, to go to Jesus. But when he saw the wind boisterous, he was afraid; and beginning to sink, he cried, saying, Lord, save me. And immediately Jesus stretched forth his hand, and caught him, and said unto him, O thou of little faith, wherefore didst thou doubt? And when they were come into the ship, the wind ceased.19

While Mark reports the same story as follows:

And when he had sent them away, he departed into a mountain to pray. And when even was come, the ship was in the midst of the sea, and he alone on the land. And he saw them toiling in rowing; for the wind was contrary unto them: and about the fourth watch of the night he cometh unto them, walking upon the sea, and would have passed by them. But when they saw him walking upon the sea, they supposed it had been a spirit, and cried out: For they all saw him, and were troubled. And immediately he talked with them, and saith unto them, Be of good cheer: it is I; be not afraid. And he went up unto them into the ship; and the wind ceased: and they were sore amazed in themselves beyond measure, and wondered.20

Significantly, both accounts begin with Jesus departing to a mountain to pray and then reference the fourth watch of the night. The fourth watch was between 3 A.M. and 6 A.M. Additionally, Mark records that it was, “about the fourth watch.” This places the occurrence around three o’clock in the morning and so we can conclude that Jesus had been in prayer most of the night, but the possibility of him sleeping is also not out of the question. The disciples in the boat are more problematic. It appears that from a literal interpretation they had been rowing for maybe six to eight hours. It seems natural that making no headway against the wind they would have beached the boat and waited for the wind to subside. Moreover, Matthew’s account of Peter stepping overboard to join Jesus on the water appears similar to a sleepwalking experience. The point is that the whole event, as recorded in Matthew and Mark, appears more akin to a dream than to reality. This will become more explicit when compared with John’s account below:

When Jesus

therefore perceived that they would come and take him by force, to make him a

king, he departed again into a mountain himself alone. And when even was now

come, his disciples went down unto the sea, And entered into a ship, and went

over the sea toward

Note that the story follows the

accounts of Matthew and Mark, but surprisingly it also has preserved a telltale

marker of its origin as a recollection of a disciple’s dream. In the final line

of the verse, it states that after Jesus got into the boat, “immediately the

ship was at the land whither they went.” This is exactly the experience one

would expect to find in a dream. The Greek word for immediately is eutheos “as soon as, forthwith, immediately,

shortly, straightway.” In keeping with the miraculous nature of the event

described in the text, it stands to good reason that it meant to denote the

boat instantly arriving at its destination once Jesus was on the ship. This

account clearly conveys the resolution of some conflict within the

sub-consciousness of the disciple having the dream. In light of the fact that

Peter, James, and John were supposedly fishermen on the

Now it came to pass on a certain day, that he went into a ship with his disciples: and he said unto them, Let us go over unto the other side of the lake. And they launched forth. But as they sailed he fell asleep: and there came down a storm of wind on the lake; and they were filled with water, and were in jeopardy. And they came to him, and awoke him, saying, Master, master, we perish. Then he arose, and rebuked the wind and the raging of the water: and they ceased, and there was a calm. And he said unto them, Where is your faith? And they being afraid wondered, saying one to another, What manner of man is this! for he commandeth even the winds and water, and they obey him.22

As was the case with the Jesus walking on the water, this account sounds more like a dream than a reality. It surely makes more sense as a dream than a miracle. We can easily imagine Peter, James, or John having such a dream. Rich in its symbolic meaning, this dream highlights Jesus in a completely consistent manner. There could have been no better story to illustrate the truth about Jesus—the symbolic truth, than these recollections of dreams about him. Nietzsche probably would have agreed with this assessment:

Raphael,

himself one of those immortal naïves, in one of his allegorical paintings

depicted that reduction of illusion to mere illusion, the original act of the

naïve artist and also of Apolline culture. In his Transfiguration,

the lower half of the painting, with the possessed boy, his despairing bearers,

the dismayed and terrified disciples reveals the reflection of eternal, primal

suffering, the sole foundation of the world: 'illusion' here is the reflection

of the eternal contradiction, of the father of all things. From this illusion

there now arises, like an ambrosial vapour, a new and

visionary world of illusion of which those caught up in the first illusion see

nothing - a radiant floating in the purest bliss and painless contemplation

beaming from wide-open eyes. its substratum, the terrible wisdom of Silenus, and we intuitively understand their reciprocal

necessity. Apollo, however, appears to us once again as the apotheosis of the principium

individuationis. Only through him does the

perpetually attained goal of primal Oneness, redemption through illusion, reach

consummation. With sublime gestures he reveals to us how the whole world of

torment is necessary so that the individual can create the redeeming vision,

and then, immersed in contemplation of it, sit peacefully in his tossing boat

amid the waves.23

Raphael,

himself one of those immortal naïves, in one of his allegorical paintings

depicted that reduction of illusion to mere illusion, the original act of the

naïve artist and also of Apolline culture. In his Transfiguration,

the lower half of the painting, with the possessed boy, his despairing bearers,

the dismayed and terrified disciples reveals the reflection of eternal, primal

suffering, the sole foundation of the world: 'illusion' here is the reflection

of the eternal contradiction, of the father of all things. From this illusion

there now arises, like an ambrosial vapour, a new and

visionary world of illusion of which those caught up in the first illusion see

nothing - a radiant floating in the purest bliss and painless contemplation

beaming from wide-open eyes. its substratum, the terrible wisdom of Silenus, and we intuitively understand their reciprocal

necessity. Apollo, however, appears to us once again as the apotheosis of the principium

individuationis. Only through him does the

perpetually attained goal of primal Oneness, redemption through illusion, reach

consummation. With sublime gestures he reveals to us how the whole world of

torment is necessary so that the individual can create the redeeming vision,

and then, immersed in contemplation of it, sit peacefully in his tossing boat

amid the waves.23

Raphael got it right! The transfiguration of Jesus is the single most important event in the whole story of his life. The final focus of this thesis will be to elucidate the transfiguration and explore its practical implications. By incorporating this concept of a tripartite brain consciousness into the biblical accounts of Jesus’ messianic mission, we can clarify many of the strange and mysterious events surrounding his life, death, and resurrection. We hope to unlock its mysterious nature and recover its true significance. In so doing we expect to unearth the original meaning of the resurrection, a meaning that has been buried for almost two thousand years. It is a meaning that only four individuals actually understood—understood completely because they were the only individuals who had actually experienced it. Jesus only shared the mystery with those three disciples “who seemed to be pillars”24 in the early church Peter, James, and John.

The transfiguration is probably the most contextually sensitive event in the New Testament. Its proper context does not exclusively depend on actions leading up to it, but equally on events following it. It is a phenomenon of the space-time continuum per se. In the months or weeks just before the transfiguration, the two most important elements affecting its context were the death of John the Baptist and Jesus' own thoughts about the nature of God's perspective on time.

It appears that

the arrest and subsequent execution of John the Baptist by Herod Antipas, as

recorded in Mark chapter 6 and Matthew chapter 14, was a critical factor in

Jesus' reassessment of his own mission. After Jesus first heard about the

execution of John, it appears that initially he also felt threatened by Herod.

To escape Antipas he and his disciples sailed across the

And the apostles gathered themselves together unto Jesus, and told him all things, both what they had done, and what they had taught. And he said unto them, Come ye yourselves apart into a desert place, and rest a while: for there were many coming and going, and they had no leisure so much as to eat. And they departed into a desert place by ship privately.26

It seems likely that Jesus and his disciples spent considerable time in Philip's territory. It was during this period, as Jesus increased in popularity and the number of his followers continued to grow that Herod Antipas apparently began to believe that a mysterious connection somehow existed between Jesus and John the Baptist:

At that time Herod the tetrarch heard of the fame of Jesus, And said unto his servants, This is John the Baptist; he is risen from the dead; and therefore mighty works do shew forth themselves in him.27

For this reason, Jesus' concerns about Herod Antipas were probably well founded and those same concerns become more ominous in Luke's account of the same situation:

And Herod said, John have I beheaded: but who is this, of whom I hear such things? And he desired to see him.28

It appears that

during the time spent in the

After John’s

death, however, Jesus must have changed his mind and decided that another

course of action was necessary to rescue the kingdom of heaven here on earth.

In casting his own life in apocalyptic terms, Jesus also assumes the role of an

apocalyptic prophet during this period. Interpreting the events of that time as

indication of evil men thwarting the

And it came to pass, as he was alone praying, his disciples were with him: and he asked them, saying, Whom say the people that I am? They answering said, John the Baptist; but some say, Elias; and others say, that one of the old prophets is risen again. He said unto them, But whom say ye that I am? Peter answering said, The Christ of God. And he straitly charged them, and commanded them to tell no man that thing;31

It was ultimately after this

affirmation by his disciples and especially Peter that Jesus came to realize he

had to sacrifice his life for the

From that time

forth began Jesus to shew unto his disciples, how

that he must go unto

After resolving

this issue in his mind and deciding on his course of action, Jesus boldly

announces to his disciples just before his transfiguration, "But I tell

you of a truth, there be some standing here, which shall not taste of death,

till they see the

Most likely

Jesus' willingness to sacrifice his life for the

Now that

the dead are raised, even Moses shewed at the bush,

when he calleth the Lord the God of Abraham, and the

God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. For he is not a God of the dead, but of the

living: for all live unto him.34

And as

touching the dead, that they rise: have ye not read in the book of Moses, how

in the bush God spake unto him, saying, I am the God

of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob? He is not the God of

the dead, but the God of the living: ye therefore do greatly err.35

But as

touching the resurrection of the dead, have ye not read that which was spoken

unto you by God saying, I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the

God of Jacob? God is not the God of the dead, but the God of the living.36

This outlook on God's perspective of time would have been completely compatible with Semitic thought patterns of the first century. In fact, such a point of view might actually underlie that culture's acceptance of a resurrection of the righteous. Thorleif Boman offers further support for this view in his book, Hebrew Thought Compared with Greek:

It is clear what meaning God's consciousness must have had for the Hebrews; the life of a man encompasses a small part of the history of existence, the life of a people a greater part, the life of humanity a still greater part, but the life of God encompasses everything. God's consciousness is a world consciousness in which everything that takes place is treasured and held fast in the eternal and is therefore as indestructible as 'matter'. Without a world consciousness, all the history of humanity and of the universe would end in nothing; for a people, however, for whom life and history is everything, the concept of a divine world consciousness is as necessary as the concept of eternal being was for the "Greeks. For the Israelites, the world was transitory, but Jahveh and his words (and deeds) were eternal (Isaiah. 40.8).

. . . For the Hebrews who have their existence in the temporal, the content of time plays the same role as the content of space plays for the Greeks. As the Greeks gave attention to the peculiarity of things, so the Hebrews minded the peculiarity of events.37

Three of the four canonical gospels give an account of Jesus' transfiguration. Only the gospel of John remains silent about its occurrence. As was the case with previously discussed miracles, a dream aspect is not entirely absent from these accounts. Luke reports that the disciples were heavy with sleep at the beginning of the event and later awaken to experience it consciously.

And it came to

pass about an eight days after these sayings, he took Peter and John and

James, and went up into a mountain to pray. And as he prayed, the fashion of

his countenance was altered, and his raiment was white and glistering. And,

behold, there talked with him two men, which were Moses and Elías:

Who appeared in glory, and spake of his decease which

he should accomplish at

Conversely, the gospels of Matthew and Mark do not mention the disciples being asleep at anytime during the event. Quite to the contrary, in their narratives the disciples appear to be wide-awake and conscious throughout the entire experience. This fact is clearly discernable in the following two accounts:

And after six days Jesus taketh Peter, James, and John his brother, and bringeth them up into an high mountain apart, And was transfigured before them: and his face did shine as the sun, and his raiment was white as the light. And, behold, there appeared unto them Moses and Elias talking with him. Then answered Peter, and said unto Jesus, Lord, it is good for us to be here: if thou wilt, let us make here three tabernacles; one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elias. While he yet spake, behold, a bright cloud overshadowed them: and behold a voice out of the cloud, which said, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased; hear ye him. And when the disciples heard it, they fell on their face, and were sore afraid. And Jesus came and touched them, and said, Arise, and be not afraid. And when they had lifted up their eyes, they saw no man, save Jesus only. And as they came down from the mountain, Jesus charged them, saying, Tell the vision to no man, until the Son of man be risen again from the dead. And his disciples asked him, saying, Why then say the scribes that Elias must first come? And Jesus answered and said unto them, Elias truly shall first come, and restore all things. But I say unto you, That Elias is come already, and they knew him not, but have done unto him whatsoever they listed. Likewise shall also the Son of man suffer of them. Then the disciples understood that he spake unto them of John the Baptist. (emphasis mine)39

Only in the following version of the transfiguration as recorded in Mark is there any mention of the disciples being confused about what “rising from the dead” meant in Jesus’ statement to them:

And after six days Jesus taketh with him Peter, and James, and John, and leadeth them up into an high mountain apart by themselves: and he was transfigured before them. And his raiment became shining, exceeding white as snow; so as no fuller on earth can white them. And there appeared unto them Elías with Moses: and they were talking with Jesus. And Peter answered and said to Jesus, Master, it is good for us to be here: and let us make three tabernacles; one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elías. For he wist not what to say; for they were sore afraid. And there was a cloud that overshadowed them: and a voice came out of the cloud, saying, This is my beloved Son: hear him. And suddenly, when they had looked round about, they saw no man any more, save Jesus only with themselves. And as they came down from the mountain, he charged them that they should tell no man what things they had seen, till the Son of man were risen from the dead. And they kept that saying with themselves, questioning one with another what the rising from the dead should mean. And they asked him saying, Why say the scribes that Elías must first come? And he answered and told Elías verily cometh first and restoreth all things; and how it is written of the Son of man, that he must suffer many things and be set at nought. But I say unto you, That Elías is indeed come, and they unto him whatsoever they listed, as it is written of him. (emphasis mine)40

While

obviously recalling the same event, three significant differences do exist

between Luke's narrative and the accounts given in the gospels of Matthew and

Mark. First, the gospel account in Luke makes no mention of Jesus instructing

his disciples to tell 'no man' about their experience of his transfiguration

until the Son of man has risen from the dead. In the gospels of Matthew and

Mark, Jesus clearly directs his disciples to remain silent until the Son of man

has risen again from the dead. Second, Luke's account makes no mention of a

discussion with the disciples, following the transfiguration, about the need

for Elijah to come and restore or reconstitute all things "before the

coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord."41 Both

Matthew and Mark detail a significant exchange between Jesus and his disciples

in which Jesus explains that Elijah has already come in the person of John the

Baptist. Finally, the gospel of Luke places the

transfiguration some eight days after a common incident recorded in all three

synoptic gospels while Matthew and Mark place it six days after the same common

incident. The incident in question is in which Jesus boldly asserts to his

disciples, “Verily I say unto you, That there be some of them that stand here,

which shall not taste of death, till they have seen the

All three of these

differences can be significant when interpreted in relationship to a brain consciousness. Based on a literal

reading of the three gospels it becomes clear that there are at least two

states of brain consciousness

depicted in the accounts. In Luke's narrative of the transfiguration, the

disciples are initially asleep (semi-conscious) while Jesus is completely awake

(cognitively conscious). This argues for the event having occurred at night, as

also was true of the previous accounts of Jesus walking on the water and

possibly, his calming the storm on the

Interpreting the

disciples' states of consciousness relative to that of Jesus is getting to the heart

of the issue with regard to Jesus' resurrection. Utilizing the idea of a

tripartite brain consciousness, in

our analysis, enables us to correlate each of the three synoptic gospels with a

corresponding state of brain

consciousness in the synaptic activity of Jesus and his three disciples. This allegorical approach is also

applicable to the Gospel of John, but in a far more abstract manner. John’s

gospel correlates more evocatively with the collective abstraction of divine

consciousness that characterizes many monotheistic religions. The differing

accounts of similar events, portrayed in each of the gospels, are an indication

of the varying degrees of consciousness associated with each of them.  Allegorically, the four gospels can also

represent symbolically the four levels of consciousness that are associated

with the biblical concepts of a first heaven and a first earth replaced by a

new heaven and a new earth. “And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the

first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea.”

(Rev 21:1)

Allegorically, the four gospels can also

represent symbolically the four levels of consciousness that are associated

with the biblical concepts of a first heaven and a first earth replaced by a

new heaven and a new earth. “And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the

first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea.”

(Rev 21:1)

This allegorical approach explains two of the three differences already identified in Luke’s account of the transfiguration. Only the difference between Luke’s report of eight days in contrast to the six days described in Matthew and Mark requires a further explanation. This explanation fully incorporates the resurrection of Jesus and correlates the two days difference with the time between Jesus' death on Friday afternoon and the empty tomb discovered early Sunday morning. The following paragraphs will clarify this further.

The next significant

difference between Luke's gospel and the narratives of Matthew and Mark relates

to the story of Jesus and his disciples in  returns

to his sleeping disciples. On the third and final time he returns, he awakens

them as the guards come to immediately arrest him (Mt 26:36-46; Mk 14:32-42).

The two additional occasions of Jesus withdrawing and returning to his sleeping

disciples symbolize the temporal recurrence of specific events that results

from a repetitive reassembling of Jesus’ self-awareness in the space-time

continuum by his temporally independent sub-conscious and semi-conscious states

of brain consciousness.

returns

to his sleeping disciples. On the third and final time he returns, he awakens

them as the guards come to immediately arrest him (Mt 26:36-46; Mk 14:32-42).

The two additional occasions of Jesus withdrawing and returning to his sleeping

disciples symbolize the temporal recurrence of specific events that results

from a repetitive reassembling of Jesus’ self-awareness in the space-time

continuum by his temporally independent sub-conscious and semi-conscious states

of brain consciousness.

Moreover and equally significant is a puzzling report found only in Mark's gospel, of a young man following close behind Jesus immediately after his arrest:

And there followed him a certain young man, having a linen cloth cast about his naked body; and the young men laid hold on him: And he left the linen cloth, and fled from them naked.(Mk 14:51-52)

Within early tradition, the young man likely symbolizes the resurrected Jesus since the Apocalypse of Peter explicitly identifies him as such when Jesus tells Peter:

But he who stands near him

is the living Savior, the first in him, whom they seized and released, who

stands joyfully looking at those who did him violence, while they are divided

among themselves.” (Apocalypse of Peter 82:27-34).43

The description of a resurrected Jesus as the young man was another attempt to explain what was unexplainable. In achieving a diachronic reassembly of his self-awareness, Jesus inaugurates God’s kingdom in a New Heaven and a New Earth. His resurrection broke the symmetry of consciousness that had defined human concepts of the Old Earth and Old Heaven. The only problem for early disciples was that two thousand years ago there was no paradigm to explain this fact.

In the account given by

Mark, this same young man reappears in the narrative sitting in the tomb when

the Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome arrive at the tomb

Sunday morning. He instructs them to go tell the disciples and especially Peter

that Jesus goes ahead of them into

The final significant difference, detectable in the synoptic gospels, occurs in the final moments of Jesus' life as he dies on the cross. The last comments made by Jesus before he dies reflect his state of mind at that moment in time. Those comments as recorded in Luke when compared to his last comments as recorded in Matthew or Mark reveal two different levels of conscious awareness and despair. In Luke's account, Jesus cried out, "Father into thy hands I commend my spirit."(Lk.23:46) In this comment, Jesus appears to be reconciled with his death. However, in Matthew and Mark he cries out in despair, "My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?"(Mt 27:46 and Mk 15:34) In this cry, Jesus reveals his surprise and anguish that God did not rescue him from the cross.

These two perspectives

reflect different points of view derived from two different states of

self-awareness that characterized Jesus' brain

consciousness while he was on the cross. In the first account as recorded

in Luke and associated with a temporally dependent cognitive state of brain consciousness, Jesus clearly

expects to die. This was his mission, his destiny. In completing this mission,

he expected to initiate the  Only

the past, only another location in space-time could shelter his soul. There,

somewhere else in space-time the synergistic combination of his sub-conscious

and semi-conscious states of brain

consciousness could reassemble his self-awareness. At another location in

space-time—at the location a year earlier, at the time of his transfiguration

on the mountaintop, there his soul would find refuge in his reassembled

self-awareness. In this recurrence, in this reassembly of his self-awareness,

Jesus transcended the level of conscious self-awareness associated with the

Gospel of Luke and achieved a level associated with the Gospel of Matthew and

Mark. From the temporal perspective of Luke’s gospel, Jesus still alive could

only be a semi-conscious dream. However, from the point of view of Jesus’ own

subjective cognitive consciousness he was once again standing on the mountain,

talking with those two figures previously mentioned in the synoptic gospels. Deutsch

Based on current theories of quantum mechanics and the possible existence of parallel universes, the two figures thought

to be those of Elijah and Moses, symbolize allegorically quantum shadows of

Jesus himself.

Only

the past, only another location in space-time could shelter his soul. There,

somewhere else in space-time the synergistic combination of his sub-conscious

and semi-conscious states of brain

consciousness could reassemble his self-awareness. At another location in

space-time—at the location a year earlier, at the time of his transfiguration

on the mountaintop, there his soul would find refuge in his reassembled

self-awareness. In this recurrence, in this reassembly of his self-awareness,

Jesus transcended the level of conscious self-awareness associated with the

Gospel of Luke and achieved a level associated with the Gospel of Matthew and

Mark. From the temporal perspective of Luke’s gospel, Jesus still alive could

only be a semi-conscious dream. However, from the point of view of Jesus’ own

subjective cognitive consciousness he was once again standing on the mountain,

talking with those two figures previously mentioned in the synoptic gospels. Deutsch

Based on current theories of quantum mechanics and the possible existence of parallel universes, the two figures thought

to be those of Elijah and Moses, symbolize allegorically quantum shadows of

Jesus himself.

From a quantum mechanical point of view, the additional events and details described in Matthew and Mark are quantum shadows of the events depicted in Luke's account. Moreover, Jesus as described in Matthew and Mark is also a quantum twin to the Jesus described in the gospel of Luke. This fact helps explain the mystery of Thomas called Didymus–Thomas the twin. In a theologically significant passage in the Gospel of John, Thomas declares, "Let us also go, that we may die with him."(Jn.11:16) In John’s gospel, Thomas is an allegorical or symbolic twin of Jesus. From that gospel’s theological perspective and in relationship to its inherent concept of divine consciousness, Jesus is a disciple of God and God is his spiritual father. By reassembling the self-awareness of Jesus in space and time, God shared his omnipresent nature with Jesus and they became one. This is the central theme expressed in the Gospel of John.

At this point, it is

important to note what is happening in the continuum of space-time as well as

within Jesus' own consciousness self-awareness. Jesus has effectively returned

to a location in his past on the continuum of space-time. In truth however,

only his brain consciousness has effectively

returned to that same pattern of synaptic activity in space-time—that pattern

which eternally characterized his transfiguration. In this explanation, we once

again see Nietzsche’s concept of the eternal recurrence in action. By his focus

on a memory of a previous event, Jesus has experienced the Eternal Return. In

his solipsistic experience, no real time-travel has taken place, no journeying

faster than the speed of light has occurred in this situation. Only Jesus' faith allows him to experience his own

resurrection. In Nietzsche’s philosophy, Jesus has now become an Übermensch by overcoming the illusion of

his own death. Following this line of reasoning further  explains

why Jesus tells Peter, James, and John that Elijah has already come and restored

all things. The vary fact that he is restored or reassembled makes restoration

a given fact. Most important, however, is the fact that he needs to tell the

disciples not to reveal what they have witnessed before he rises again from the dead. Since

the three disciples had not yet died, Jesus knew they also had not yet

completed his journey; it was still in their future. However, on the third day

following his death the cognitive consciousness of Peter, James and John would

have completed their journey. Synchronized in space-time with a delay of two

days between Jesus’ death and resurrection is the difference

of two days between Luke's claim that the transfiguration occurred eight

days after Peter’s affirmation and Matthew’s and Mark’s claim that it occurred

six days later. Critical to properly understanding this account, is the

recognition that only three disciples share this common point in the space-time

continuum with Jesus. Peter, James, and John are the only individuals who will

have any inkling of what is happening. Jesus knows this and effectively plans

for it by planting a seed in their minds when he instructs them, "Tell the vision to no man until the Son of man be risen again

from the dead."(Mt 17:9)

explains

why Jesus tells Peter, James, and John that Elijah has already come and restored

all things. The vary fact that he is restored or reassembled makes restoration

a given fact. Most important, however, is the fact that he needs to tell the

disciples not to reveal what they have witnessed before he rises again from the dead. Since

the three disciples had not yet died, Jesus knew they also had not yet

completed his journey; it was still in their future. However, on the third day

following his death the cognitive consciousness of Peter, James and John would

have completed their journey. Synchronized in space-time with a delay of two

days between Jesus’ death and resurrection is the difference

of two days between Luke's claim that the transfiguration occurred eight

days after Peter’s affirmation and Matthew’s and Mark’s claim that it occurred

six days later. Critical to properly understanding this account, is the

recognition that only three disciples share this common point in the space-time

continuum with Jesus. Peter, James, and John are the only individuals who will

have any inkling of what is happening. Jesus knows this and effectively plans

for it by planting a seed in their minds when he instructs them, "Tell the vision to no man until the Son of man be risen again

from the dead."(Mt 17:9)

Jesus, enlightened by his first encounter with death as described in Luke’s account, would likely not have anticipated a second death, but more likely would have expected God to establish his kingdom immediately on the earth. From the state of consciousness that is associated with Matthew and Mark, Jesus is essentially re-experiencing his transfiguration as well as the entire course of events from that moment until his death on the cross. In this heightened state of sensitivity to life, pain and disappointment are also more severe. From the perspective of a reassembled self-awareness, Jesus does indeed withdraw and return an additional two times to find his disciples sleeping in Gethsemane. It is this expectation, the expectation inherent in his higher consciousness that probably results in his soul-emptying despair on the cross as reflected in the accounts of Matthew and Mark. At the level of consciousness associated with Luke, reconciliation with his death was possible; from the higher consciousness corresponding to the gospels of Matthew and Mark, no such acceptance was forthcoming. From this cognitive state of consciousness, his anguished cries revealed only his dejection and despair, dejection and despair more severe than a moment before since God had not intervened to institute His kingdom. Even at this level of reassembled self-awareness, God had not saved him! Death was still utter desolation. For this reason, Jesus continued to seek refuge in his transfiguration and therefore he was still on the mountain with his quantum shadows of self-awareness. In all likelihood, the proto-orthodox concepts of a trinity as well as the other doctrinal confusions about the true nature of Jesus derive from this inexplicable occurrence. Without access to modern theories of quantum mechanics and cosmology, the nature of Jesus remained an unfathomable mystery to the people two thousand years ago. In portraying Jesus with Elijah and Moses, the synoptic gospels convey through a symbolic or allegorical means that God’s universe does not object nor does it prevent Jesus from being both dead and alive in the sight of God and himself. In this fact, Jesus ultimately finds his salvation as described in Mark’s gospel. (Mk14:51-52)

Up to this point, the theoretical analysis has focused almost exclusively on the possible interaction between the space-time continuum and the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus in relation to his own subjective self-awareness. As an isolated solipsistic experience for Jesus, this interplay might never have affected anyone else had it not been for the three disciples with whom he decided to share his experience. The majority of his followers would most likely have remained unchanged by these events and Christianity would have never developed into a religion of the world had Peter, James, and John not been with him two thousand years ago on that mountaintop. We now turn to their story.

Mark records that as soon as Jesus was arrested “they all forsook him, and fled.” (Mk.14:50) Only Peter remains at a safe distance behind until out of fear even he abandons Jesus. Luke records:

Then took they him, and led him, and brought him into the high priest's house. And Peter followed afar off. And when they had kindled a fire in the midst of the hall, and were set down together, Peter sat down among them. But a certain maid beheld him as he sat by the fire, and earnestly looked upon him, and said, This man was also with him. And he denied him, saying, Woman, I know him not. And after a little while another saw him, and said, Thou art also of them. And Peter said, Man, I am not. And about the space of one hour after another confidently affirmed, saying, Of a truth this fellow also was with him: for he is a Galilaean. And Peter said, Man, I know not what thou sayest. And immediately, while he yet spake, the cock crew. And the Lord turned, and looked upon Peter. And Peter remembered the word of the Lord, how he had said unto him, Before the cock crow, thou shalt deny me thrice. And Peter went out, and wept bitterly. (Lk.22:54-62)

At this point in Luke’s narrative, it is very

possible that most of the disciples were not clear about what Jesus was

actually attempting to accomplish in

And after the sop Satan entered into him. Then said

Jesus unto him, That thou doest, do quickly. Now no man at the table knew for

what intent he spake this unto him. For some of them

thought, because Judas had the bag, that Jesus had said unto him, Buy those

things that we have need of against the feast; or, that he should give something

to the poor. He then having received the sop went immediately out: and it was

night. Therefore, when he was gone out, Jesus said, Now is the Son of man

glorified, and God is glorified in him. If God be glorified in him, God shall

also glorify him in himself, and shall straightway glorify him. (Jn.13:26-32)

From this account, it

appears likely that Jesus planned his own arrest and execution in the

expectation that doing so would institute the

Behold we go up to

Luke records immediately following this passage, that the disciples "understood none of these things: and this saying was hid from them, neither knew they the things which were spoken." (Lk.18:34)

Not understanding Jesus'

mission nor sharing his expectations, the disciples naturally feared for him

and themselves as events unfolded rapidly following Jesus' arrest. During the crucifixion, most of them remained

far removed or hidden from the authorities. Luke reports that "all his

acquaintance, and the women that followed him from

In such a horrific environment of fear, Jesus' arrest and execution likely paralyzed and dismayed the disciples. For two thousand years, this solitary failure has been the main reason Judaism has never accepted the story of Jesus as being also the story of God's Messiah. Whatever occurred two thousand years ago must also account for the historical fact of Judaism's stubborn resistance to accepting these narratives as theological truth.

From a certain perspective, from that level of consciousness previously correlated with Luke's gospel the entire episode must have seemed a disastrous mistake. After Jesus died that Friday it was all over, everything died with him that afternoon. The mission had failed, the master of the plan destroyed, and the whole experience had been a personal apocalypse for Jesus and his followers.

Out of this reality, something else emerged, something subjectively marvelous, but objectively inadequate. Some incredible event occurred, but in its incredulity, it was initially not sufficient to convince all of humanity that the executed Jesus had risen from the grave and was once again alive. The history of Judaism supports that proposition. To understand the event, requires a return to the consciousness of Jesus and of his three disciples who shared a common moment in the space-time continuum with him on the mountain.

As discussed in previous paragraphs, when Jesus died that Friday afternoon his cognitive consciousness ended; however, his sub-conscious and semi-conscious states of brain consciousness reassembled his synaptic patterns into the recurring self-awareness that had characterized his life a year earlier when he was on the mountain with Peter, James, and John. Those three disciples also had a cognitively conscious experience at that earlier time, but their present reality had replaced it. Subsequent patterns of synaptic activity had replaced it and converted it into a long-term memory that was now devoid of any present self-awareness. For Jesus however, as death approached and his cognitive consciousness focused on remembering that previous moment, that focused memory became a reassembled self-awareness. Emptied by death but now awash in remembered sensations that memory became his present reality. Had the three disciples shared his death they would have also shared his resurrection on the mountain. Again, we see the significance of the earlier reference to Thomas, the quantum shadow of Jesus who said, "Let us also go, that we may die with him." (Jn.11:16) Nonetheless, only those three disciples shared that common cognitively consciousness state with Jesus. According to the theoretical analysis, when the women reported the empty tomb to the disciples, as is recorded in Matthew, Luke, and John only the three disciples Peter, James, and John would have had a conscious memory in common with Jesus at both locations on the space-time continuum. Only they would share a sub-conscious and semi-conscious state of brain consciousness with Jesus. Most likely upon hearing of the empty tomb, in an instant of incredible insight Peter, James, John would have re-experienced their mountain moment subconsciously and clearly remembered Jesus' directions to them as they had come down from that mountain, "Tell the vision to no man, until the Son of man be risen again from the dead."

Here we find clearly the motivation behind the miraculous events that cascaded from that moment. Acting on their inexplicable and yet astonishing insight, the three disciples lead the others back to that mountain to discover why their recollections of it formed their most intense and clear memories of Jesus. In fact, as soon as Jesus died on the cross, theoretically, the three disciples would have started to become confused as their present memories of Jesus blended together with their past memories of his transfiguration in a profound and perplexing manner. Initially thought to be a reaction to the arrest and execution of Jesus, the confusion was probably more the result of sharing their sub-conscious and semi-conscious states of brain consciousness with Jesus as he experienced his own reassembly that that location in space-time. In transcending his own death Jesus’ consciousness also raised the consciousness of his three disciples because they shared that cognitive conscious moment in the space-time continuum. As their consciousness continued to interlace these parallel lines of cosmic history, the three disciples became more fervent in their belief that Jesus was indeed alive and by his faith, he truly had risen from the dead.

In the final verses of Matthew 28:16-20, the reported actions of the disciples are completely compatible with this or some similar scenario:

Then the eleven disciples

went away into

Those who doubted what the others saw were the disciples who did not share the experience with Jesus’ transfiguration. No common experience anchors them with Jesus’ resurrection on the space-time continuum. However, the faith and convictions of Peter, James, and John were beyond doubt. Therefore, it was only a matter of time before others would come to experience Jesus also in one form or another. The physical reality, however, was an objective reality only for those three disciples “who seemed to be pillars” in the church according to Paul. Through their experience Jesus had shared the truth with them—the truth that God’s universe does not object nor does it prevent Jesus from being both dead and alive in the sight of God and himself, and now in the sight of those three disciples also.

Two additional accounts further substantiate this proposed reconstruction of the events surrounding the resurrection of Jesus by locating post resurrection sightings or encounters upon a mountain. The first account is by the author of the gospel of Luke. He records in the Acts of the Apostles:

And when he had spoken

these things, while they beheld, he was taken up; and a cloud received him out

of their sight. And while they looked steadfastly toward heaven as he went up,

behold, two men stood by them in white apparel; . . . Then returned they unto

While the actual mountain was supposedly the

The second account comes from a Gnostic document discovered in the Nag Hammadi Library, "The Sophia of Jesus Christ".

After he rose from the

dead his twelve disciples and seven women continued to be his followers and

went to

In final analysis, the tendency to cast post resurrection encounters within the context of an event occurring on a mountain is traceable to Matthew's post resurrection account.

Notes

CHAPTER FOUR

1. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ, trans. R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Viking Penguin Books, 1968), 146.

2. Ibid., 144-5.

3. Ibid., 147-8.

4. Ibid., 147.

5. Ibid., 151.

6. Ibid., 149

7. Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 73.

8. Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ, 154.

9. Ibid., 129.

10. Ibid.

11. Jacques Le Goff, The Medieval Imagination, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 199.

12. Ibid., 207.

13. Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, 45.

14. Le Goff, 197.

15. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, ed. Michael Tanner, trans. Shaun Whiteside (London: Penguin Books, 1993), 25.

15. Calming the tempest in the Sea

of Galilee: Mt 8:24, Mk 4:38, Lk 8:23, In

16. Raising Jairus’ daughter: Mt 9:24, Mk 5:39, Lk 8:52, Story of Lazarus: Jn 11:11, Upon Jesus’ death: Mt 27:52 AV

17. Le Goff, 196.

18. Bart D. Ehrman,

Lost Christianities: The

19. Mt 14:23–32 AV

20. Mk 6:45-51 AV

21. John 6:15-21 AV

22. Luke 8:22 - Luke 8:25 AV

23. Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, 25-6.

24. Gal 2:9 AV

25. Mt 14:13 AV

26. Mk 6:30-32 AV

27. Matthew 14:1-2 AV

28. Luke 9:9 AV

29. Mt 10:7 AV

30. Mt 11:12 AV

31. Luke 9:18-21 AV

32. Mt 16:21 AV

33. Luke 9:27 AV

34. Luke 20:37-38 AV

35. Mk 12:26-27 AV

36. Mt 22:31-32 AV

37. Thorleif Boman, Hebrew Thought Compared with Greek, trans. Jules L. Moreau (New York: Norton, 1970), 139.

38. Luke 9:28-36 AV

39. Mt 17:1-13 AV

40. Mk 9:2-13 AV

41. Mal 4:5 AV

42. Mark 9:1 AV

43. James M. Robinson, ed., The Nag Hammadi Library in English, 3d ed., rev., “Apocalypse of Peter”, trans. James Brashler and Roger A. Bullard (San Francisco, Harper & Row, 1988), 377

44. James M. Robinson, ed., The Nag Hammadi Library in English, 3d ed., rev., “The Sophia of Jesus Christ”, trans. Douglas M. Parrott (San Francisco, Harper & Row, 1988), 222

Send your thoughts and comments to us: forum@mountdivination.net